Gone are the days when authors could only see their books in the hands of readers if they won the favour of a major publishing house.

In the 21st century, authors can go directly to their readers and sell their work at the price they set. That means higher royalties and more control over the product – but a greater reliance on reviews. Writers need to prove the books are just as good as their traditionally published cousins.

For the last few years, indie publishing has been seen as the last resort of desperate writers. Critics bemoan the lower cost of entry to what was previously a highly regulated industry.

But has indie publishing finally overcome the stigma and come of age as a viable alternative? Let’s take a look at the history of indie publishing.

Getting into bookstores is often still the dream [Public domain, via Pixabay]

What’s the difference between indie publishing and vanity publishing?

Vanity publishing dates back far beyond indie publishing. In fact, Jane Austen paid Thomas Edgerton to publish Sense & Sensibility in 1811. That essentially demonstrates the difference between indie and vanity publishing.

Vanity publishing is the process of paying someone to turn your manuscript into a product. They won’t do any editing or marketing for you, and there’s a danger you’ll end up with a garage full of boxes of your books.

It’s also one of the reasons why so many people still don’t see indie publishing as a valid model. In a pay-to-play model, anyone with enough money could theoretically turn their manuscripts into books.

By comparison, indie publishing involves organising all of the tasks associated with publishing yourself. That doesn’t mean you have to do them – in fact, you really should hire a cover designer and an editor, if nothing else – but you’re in charge of seeing they happen.

You’re a one-person publishing house for your own books.

It still means that anyone can put out a book because the process bypasses the gatekeepers of traditional publishing – the agents and the submissions pile.

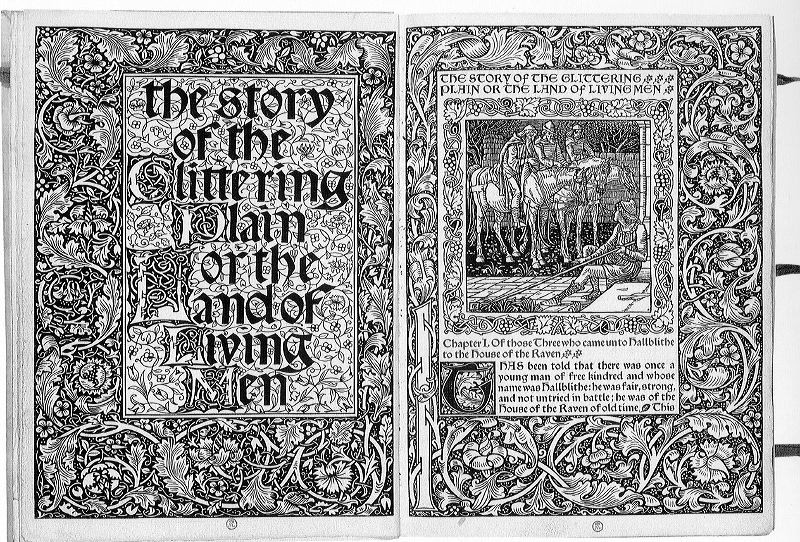

But indie publishing is not a new thing. William Morris, one of the main driving forces of the Arts and Crafts Movement, founded his own Kelmscott Press in 1890. While he didn’t publish books that he wrote himself, having his own press gave him full artistic control over the books his press did produce.

By William Morris († 1896) [Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons]

And Virginia Woolf founded her own press, Hogarth Press, in 1917 to give her full control over her artistic vision. If it’s good enough for them...it’s good enough for you.

The game has changed

Despite the occasional foray into indie publishing, for the bulk of the 20th-century publishing relied on the big houses. Authors fought to get published by the likes of Penguin and Random House.

It wasn’t easy. Stephen King’s Carrie, now considered a masterpiece, was rejected 30 times until Doubleday Publishing picked it up.

J. K. Rowling’s transition from nobody to megastar through a chance encounter between an assistant and the slush pile has become publishing legend.

But for most writers, you needed an agent or a publishing contract. Preferably both. The technology didn’t really exist to publish anything yourself unless you were wealthy. And vanity publishing was seen as the last resort of the desperate.

Print on demand technology (or POD) was one of the main game-changers in indie publishing. Lightning Source was founded as long ago as 1997, and it allowed authors to upload manuscripts that would literally only be printed when they were needed.

Suddenly, you didn’t need several thousands of dollars to print a few hundred copies of a book that you might never sell. All you needed to do was generate the demand, and the books would come later.

Technology finally caught up

But it wasn’t until 10 years later that the potential of indie publishing really had the technology to back it up.

Enter the Kindle. Released to a fanfare in 2007, the first models sold out in less than 6 hours.

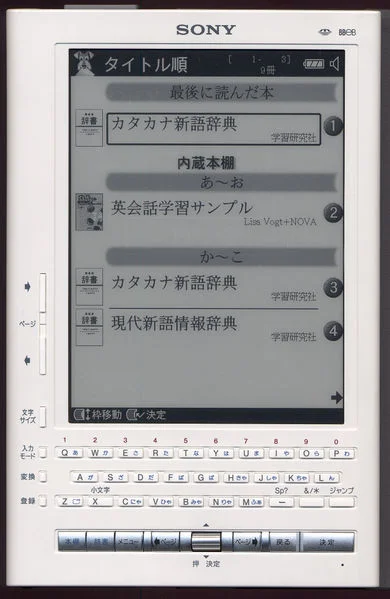

Amazon wasn’t the first company to investigate e-readers. Sony invented the first e-reader that used E Ink in 2004 with the Sony Librie.

The Sony Librie, by Dale DePriest [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0), via Wikimedia Commons]

The advantage of the Sony Reader was its ability to display PDFs, ePub books, RSS newsfeeds and even jpg files. Some of them could even play mp3 files.

With celebrities like Demi Moore discussing the wonders of the Kindle, the device soon outstripped the technically more advanced Sony offering. In 2014, Sony announced it would no longer makeconsumer e-readers.

But the existence of the Sony e-reader meant readers – and authors – weren’t restricted to a single file format. Smashwords was founded in 2008 to provide books in multiple formats. It gave greater flexibility to readers, particularly those who didn’t want to support Amazon.

Barnes & Noble released the Nook in 2009. In 2010, the first iPad hit stores. The Kobo arrived in 2011. Readers had a whole new way to buy books for their new favourite device.

Authors were initially slow to throw books onto these electronic bookstores. Amanda Hocking is often cited as the first real success story, held up as a poster girl for self-publishing. Hocking’s novels had been rejected by agents, but she self-published her first four titles in April 2010. She’d earned enough to quit her day job by August that same year.

Authors suddenly realised that they didn’t need to play the publisher’s game. Most estimates put the so-called Kindle Revolution at 2011. The rules had changed.

The Kindle is the most popular e-reader [Public domain, via Pixabay]

The new professionalism

The public soon tired of badly edited, badly formatted self-published titles. Self-publishing earned a reputation that put it on par with vanity publishing. Some believed that only people who couldn’t get traditional deals would resort to self-publishing.

And in some quarters, the bad reputation hasn’t entirely dissipated. Many still sniff at indie published titles, assuming they will be poor quality. Sadly, there are still authors publishing books that don’t meet the standard.

Thankfully, most authors have realised that they need to produce a professional product if they want to compete with the big publishing houses. For many readers, it’s difficult to distinguish between traditional and indie products – aside from the price. Philip Pullman’s The Book of Dust is available for pre-order at £9.99 for an e-book on Amazon. Many indie published titles are available for £3.99 or much less.

And traditional publishing is no longer the only way to achieve greater success.

Hugh Howey chose to indie publish his Wool series because of the freedom of the process. But he still managed to sell the film rights to 20th Century Fox. He signed a print-only deal with Simon & Schuster to access distribution to US book retailers. But he still distributes Wool online himself. He’s one of the ‘hybrid’ authors who works across both forms of publishing.

The Wool Omnibus. By Hugh C. Howey (Hugh C. Howey's blog) [CC0, via Wikimedia Commons]

And science fiction writer Andy Weir landed a film deal for The Martian after serialising the novel on his blog. He only signed the traditional deal for the novel some three years after putting the story online.

Many have renamed the movement ‘indie publishing’ due to the change in professionalism. Writers are no longer self-publishing, per se. They’re simply publishing independently from the big publishers.

And successful indie authors can command higher royalties than their traditionally published counterparts.

In 2016, indie author Joanna Penn earned approximately £66,000 in book sales alone. Penn points out herself that her "books are rarely in the top sales ranking on Amazon" but her income isn’t to be sneezed at.

In mid-2016, crime author Adam Croft reportedly pulled in around £2,000 a day in royalties.

While many indie published writers can only dream of such high payouts, it’s still easier to make more money simply due to the royalty structure. For a book priced above £2.99 on the Amazon Kindle store, authors net a cool 70%. Compare that to many traditional deals, which only pay out 10% in royalties (though perhaps due to the pressure of independent publishing, some publishers are now offering 50% e-book royalties).

Indie publishing is an industry in itself

Authors are no longer simply wordsmiths hammering away at the keyboard until something resembling a book appears. Authors do their own marketing, design their own websites, and hire their own collaborators. In the world of indie publishing, you’ll get to know editors, proof-readers, cover designers, book formatting specialists, and other authors to help you spread the word.

All of these hats require a level of professionalism that have earned indie publishing a reprieve from, if not yet a total reversal of, its previous poor reputation.

And it’s about time.

Need help preparing your book for publication? I offer a full range of editorial services – from developmental editing to proofreading the cover or product description. I can offer guidance through the publication and distribution process and help you create a professional book marketing strategy.